Python Basics

This page will go over the basics of python. It is meant to be quick and getting your feet wet. If you are interested in more details of topics feel free to use Google. This should be enough information here to start out doing some easy leetcode questions This tutorial will go over Python 3+ as it is the most recent one.

Download Python

To download python go to Download and download the version for your OS

Install IDE

There are several different types of IDE’s for python:

We use VSCode for this tutorial as it has functions for multiple other languages and is not only for python

Basics

Print function

The print() function in python is used to print specified message on the screen. It can print strings or objects which are then converted to a string while on the screen

Examples:

Input

print ("HELLO ZOOFYTECH")

Output

HELLO ZOOFYTECH

Input

print("ABC")

print("123")

print("xyz")

print("890")

Output

ABC

123

xyz

890

Input

print ("Hello\nWorld")

The \n will put a new line

Output

Hello

World

Execute Scripts

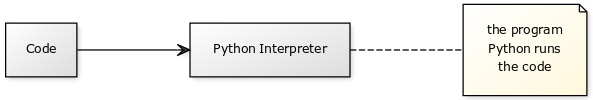

To run Python programs, you will need the Python interpreter and possibly an editor(IDE).

A Python interpreter executes Python code (sometimes called programs).

A program can be one or more Python files. Code files can include other files or modules. To run a program, you need to specify a parameter when executing Python.

There are several ways to execute a python file.

- Execute the file using

pythoncommand on terminalpython hello.py - If the file has a shebang on the first line to call the python interpreter such as

#!/usr/bin/env python3or#!/usr/bin/python3then you can run the script by just typing in the file name as long as it is executable. To make it executable first runchmod +x hello.pythen runhello.py - Run on from IDE. On the IDE you can run the program. On vscode right click the file you are in and run it in interactive mode(this will require install of jupyter notebook)

Variables

A Python variable is a reserved memory location to store values. Every value in Python has a datatype. The following are the different types: integers (numbers), float (decimal numbers), booleans (true or false) and strings (text). Variables in Python can be declared by any name or even alphabets like a, aa, abc, etc.

Below are some examples of variables. Please try them out on your IDE

Example 1

# This is a comment

# a is the variable

a=900

print (a)

Example 2

b=2

print(b)

# re-declaring the var to 3 and printing it

b=3

print(b)

Example 3

Concatenation is only possible if you use the same type of datatype.

a=100

b="cool people"

# This will fail

print a+b

One can change the integer to a string by putting a str before it

a=100

b="cool people"

print(str(a)+b)

Example 4

There are two types of variables in Python, Global variable and Local variable. When you want to use the same variable for the entire program or module you declare it as a global variable.

To set a global variable, it must be outside of a function. We’ll talk more about functions later

Note:

For best practices, people tend to set global variables using all capital letters

GLOBAL_VAR=200

print(GLOBAL_VAR)

# Create function called funFunction

def funFunction():

print(GLOBAL_VAR)

# Call the function

funFunction()

Example 5

To change a global variable inside a function use the global keyword

GLOBAL_VAR=200

print(GLOBAL_VAR)

# Create function called funFunction

def funFunction():

global GLOBAL_VAR

GLOBAL_VAR="new global var"

print(GLOBAL_VAR)

# Call the function

funFunction()

Example 6

You can also delete variables using the del command

l =11

print(l)

del l

print(l)

The above should output NameError: name 'l' is not defined

Strings

Python can manipulate strings which can be expressed in several ways. Strings can be enclosed in single quotes '..' or double quotes ".." and \ can be used to escape special characters such as quotes

print('hello') #single quote

print("world") # Double quote

print('it doesn\'t have to be this fun') # use \ to escape quote

print("it doesn't have to be this fun" # or just use double quotes instead)

print('"No," yes!')

Strings prefixed with r or R, such as r'...' and r"...", are called raw strings and treat backslashes \ as literal characters. In raw strings, escape sequences are not treated specially.

print(r'a\tb\nA\tB')

print('a\tb\nA\tB')

You can also use triple quotes for multiple lines such as """...""" '''...'''

print("""

Usage: [OPTIONS]

-h Display this usage message

-H hostname Hostname to connect to

""")

Strings can be concatenated (glued together) with the + operator, and repeated with *:

print(3*'hi') # 3 times hi

print("hello" + "man") # print helloman

Two or more string literals next to each other are automatically concatenated This is great for breaking long strings:

long_string= ('lets put some very long strings in different lines '

'but put them together by concatenation')

print(long_string)

It only works for two literals though not variables. If you want to concatenate variables or a variable and literal then you can use the +

a='cats'

print(a + " and dogs")

Strings can be indexed with the first character having an index of 0.

word="verylongword"

print(word[0])

print(word[-1]) # can go negative for the last character

print(word[-12]) # print the first character

print(word[-2]) # print 2nd to last character

Strings can also be sliced. While indexing is used to get individual characters, slicing allows you to get multiple strings:

word="verylongword"

print(word[0:2]) # prints positions 0-2

print(word[2:5]) # prints positions 2-5

print(word[:2]) # prints positions from beginning to position 2(excluded)

print(word[3:])# prints position 3 until end(included)

print(word[-2:]) # prints positions second to last until end

Note how the start is always included, and the end always excluded. This makes sure that s[:i] + s[i:] is always equal to s:

word="verylongword"

print(word[:2])

print(word[2:])

print(word[:2] + word[2:])

Strings cannot be changed as they are immutable. Therefore, assigning to an indexed position in the string results in an error:

word[0]='J' #this will fail

word[2:]='test' #this will also fail

The built in function len returns the length of a string

word='verylongword'

len(word)

Numbers

There are three numeric types in Python:

intInt, or integer, is a whole number, positive or negative, without decimals, of unlimited length.floatFloat, or “floating point number” is a number, positive or negative, containing one or more decimals. Float can also be scientific numbers with an “e” to indicate the power of 10.complexComplex numbers are written with a “j” as the imaginary part:

Variables of numeric types are created when you assign a value to them:

a = 6 # int

b = 9.28 # float

c = 5j # complex

print(type(a)) # Use type to see what type it is

print(type(b))

print(type(c))

Converting

You can convert from one type of number to another with int(), float(), and complex() methods:

a = 6 # int

b = 9.28 # float

c = 5j # complex

#convert from int to float:

d = float(a)

#convert from float to int:

e = int(b)

#convert from int to complex:

f = complex(c)

print(d)

print(e)

print(f)

print(type(d))

print(type(e))

print(type(f))

Python also has a module called random that can be used to make random numbers

import random

print(random.randrange(1,10))

Python also has a built in simple calculator. You can use expressions of operators like +, -, *, /

print(2+2)

print((50 -5*5)/4)

print(5/2)

There is also floor division where it rounds down the numbers instead of having a float

print(15//4) ## floor division

print(15/4) ## regular division

It is also possible to calculate power by using **

print(5 ** 2)

print(10 ** 2)

Lists

Lists are a way to store multiple items in a single variable

Lists are one of the 4 built in data types for Python used to store collections of data. The other 3 are Tuple, Set, and Dictionary

Lists are created using square brackets [] with comma separated values

names = [john, amy, george ]

print(names)

In python, lists are very flexible you can do things like concatenation, replace, append, slice and much more..

concatenation

numbers = [1,2,3,4]

connums = numbers + [5,6,7,8]

print(connums)

replace

odd_nums = [1,2,5,7,9]

odd_nums[1] = 3

print(odd_nums)

append

odd_nums = [1,2,5,7,9]

odd_nums[1] = 3

print(odd_nums)

odd_nums.append(11)

odd_nums.append(13)

print(odd_nums)

slice

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g']

# replace some values

letters[2:5] = ['C', 'D', 'E']

print(letters)

# now remove them

letters[2:5] = []

print(letters)

#clear all except first letter

letters[0:] = []

print(letters)

Replace

Python has a built in support for string replacement. A string is variable that contains text data. To replace a string call the string.replace(old,new) method using the string object

a = "Hello World"

s = s.replace("World", "Universe")

print(s)

An optional parameter is the number of items that will be replaced. By default it is all

a = "Hello World World World"

s = s.replace("World", "Universe", 1)

print(s)

Join

The join method joins elements and returns them combined as a string.

firstname = "John"

lastname = "Doe"

sequence = (lastname,firstname)

name = " ".join(sequence)

print(name)

It can also join a list of words as well:

list = ["cat","dog","bunny","rabbit"]

animals= ' '.join(list)

print(animals)

String find

The find() method searches for query string and returns the character position if found. If no string is found, it returns -1.

You can add a string index and end index: `find(query,start,end), but these parameters are optional

Example:

s = "Today is a good day"

index = s.find("good")

print(index)

You can also use _in_ to search for strings

s = "Today is a good day"

if "good" in s:

print("query found")

Split

A string can be split into substrings using the split(param) method. This method is part of the string object. The parameter is optional, but you can split on a specific string or character.

If you have a string, you can subdivide it into several strings. The string needs to have at least one separating character, which may be a space.

By default the split method will use space as separator. Calling the method will return a list of all the substrings.

s = "Split this sentence"

words = s.split()

print(words)

if you want to split a word into characters, use the list method:

word = "word"

x = list(word)

print(x)

Read input

The input function will ask for keyboard input from the user. The functions read input from the keyboard, converts it to a string and removes the newline(Enter)

name = input('What is your name? ')

print('Hello ' + name)

job = input('What is your job? ')

print('Your job is ' + job)

num = input('Give me a number? ')

print('You said: ' + str(num))

Flow Control

if statements

In Python the if statement is used for conditional execution or branching. An if statement is one of the control structures. (A control structure controls the flow of the program.)

The if statement may be combined with certain operator such as equal (==), greater than (>=), less than (<=) and not equal (!=). Conditions may be combined using the keywords or and and.

A basic statement should look like this:

if <condition>:

<statement>

- is the condition evaluated as a Boolean, it can either be True or False.

- if it is one more lines of code. Each of those lines must indented with four spaces.

Examples:

x = 4

if x < 10:

print('x is less than ten')

if x > 10:

print('x is greater than ten')

if x > 1 and x < 5:

print('x is in greater than 1 and less than 5')

multiple statements An if statement doesn’t need to have a single statement, it can have a block. A block is more than one statement. In python blocks are defined by indentations.

if <condition>:

<statement>

<statement>

<statement>

<statement> # not in block

Example

x=10

if x < 11:

print("x is less than 11")

print("this means it's not equal to 11 either")

print("x is an integer")

If-Else

The else keyword is used typically when all other cases are done.

num = input("Pick a number 1-10 \n")

if num <= "10" and num >= "1":

print("Your number is " + num)

else:

print("Please choose a number between 1-10")

elif

If you want to evaluate several cases, you can use the elif clause. elif is short for else if. Unlike else, with elif you can add an expression.

That way instead of writing if over and over again, you can evaluate all cases quickly

x=1

if x == 2:

print('two')

elif x == 1:

print('one')

elif x == 4:

print('four')

else:

print('x is equal to ' + x)

It all boils down to how people read things because the above is the same as the example below

x=1

if x == 2:

print('two')

if x == 1:

print('one')

if x == 4:

print('four')

else:

print('x is equal to ' + x)

for loops

A for loop repeats an action that can have 1 or more instructions. In python for loops iterates over the items of any sequences(lists, strings, dictionaries) in the order that they appear in the sequence.

city= ['New York', 'San Francisco', 'Hong Kong']

print ('Cities : ')

for i in city:

print('City: ' + i)

# Create a sample collection

users = {'John': 'active', 'Rob': 'inactive', 'Ken': 'active'}

active_users = {}

for user, status in users.items():

if status == 'active':

print(user+ ":" + status)

while loops

While loops are used to repeat execution as long as the expression is true

while_stmt ::= "while" assignment_expression ":" suite

["else" ":" suite]

This repeatedly tests the expression and if it is true, executes the first suite; if the expression is false the suite of the else clause,if present is executed and loop is terminated. A break statement executed in the first suite terminates the loop without executing the else clause’s suite. A continue statement executed in the first suite skips the rest of the suite and goes back to the testing expression

x = 4

while x < 10:

print(x)

x = x + 1

# This will loop through the numbers until it reaches 10 but excludes 10

Nested loops

A loop can contain one or more other loops. You can create a loop inside a loop. This principle is known as nested loops. Nested loops can get a bit confusing especially if it goes over 3 deep

example

people = [ "John", "Jim", "Peter", "Jason" ]

restaurants = [ "Japanese", "American", "Mexican", "Chinese" ]

for person in people:

for restaurant in restaurants:

print(person + "eats " + restaurant)

exceptions

Python has built-in exceptions which can output an error. If an error occurs while running the program, it’s called an exception.

If an exception occurs, the type of exception is shown. Exceptions needs to be dealt with or the program will crash. To handle exceptions, the try-catch block is used.

All exceptions in Python inherit from the class BaseException. If you open the Python interactive shell and type the following statement it will list all built-in exceptions:

dir(builtins)

except

The idea of the try-except clause is to handle exceptions (errors at runtime). The syntax of the try-except block is:

try:

<do something>

except Exception:

<handle the error>

- try: the code with the exception(s) to catch. If an exception is raised, it jumps to the except block.

- except: this code is only executed if an exception occurred in the

tryblock even if it contains only the pass statement

it can also be combined with the else and finally keywords.

- else: Code in the else block is only executed if no exceptions were raised in the try block.

- finally: The code in the finally block is always executed, regardless of if an exception was raised or not

try

The try-except block can handle exceptions. This prevents the program from crashing and exiting in errors.

try:

1 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('One divide by zero')

print('This should still print')

After the except block, the program continues. Without a try-except block, the last line would not print and crash.

You can also write different logic for each type of exception that happens:

try:

# your code here

except FileNotFoundError:

# handle exception

except IsADirectoryError:

# handle exception

except:

# all other types of exceptions

print('This should still print')

finally

A try-except block can have the finally clause. The finally clause is always executed

try:

<do something>

except Exception:

<handle the error>

finally:

<cleanup>

Say if you’d want to open a file then close it.

try:

f = open("test.txt")

except:

print('Could not open file')

finally:

f.close()

print('This should still print')

else

The else clause is executed if and only if no exception is raised. This is different from the finally clause that’s always executed.

try:

x = 10

except:

print('Failed to set x')

else:

print('No exception occurred')

finally:

print('This will always print')

raise

Exceptions are raised when an error occurs, but in python you can also force an exception to occur using raise

raise MemoryError("Out of memory")

raise ValueError("Wrong value")

built in exceptions

Exception Cause of Error

AssertionError if assert statement fails.

AttributeError if attribute assignment or reference fails.

EOFError if the input() functions hits end-of-file condition.

FloatingPointError if a floating point operation fails.

GeneratorExit Raise if a generator's close() method is called.

ImportError if the imported module is not found.

IndexError if index of a sequence is out of range.

KeyError if a key is not found in a dictionary.

KeyboardInterrupt if the user hits interrupt key (Ctrl+c or delete).

MemoryError if an operation runs out of memory.

NameError if a variable is not found in local or global scope.

NotImplementedError by abstract methods.

OSError if system operation causes system related error.

OverflowError if result of an arithmetic operation is too large to be represented.

ReferenceError if a weak reference proxy is used to access a garbage collected referent.

RuntimeError if an error does not fall under any other category.

StopIteration by next() function to indicate that there is no further item to be returned by iterator.

SyntaxError by parser if syntax error is encountered.

IndentationError if there is incorrect indentation.

TabError if indentation consists of inconsistent tabs and spaces.

SystemError if interpreter detects internal error.

SystemExit by sys.exit() function.

TypeError if a function or operation is applied to an object of incorrect type.

UnboundLocalError if a reference is made to a local variable in a function or method, but no value has been bound to that variable.

UnicodeError if a Unicode-related encoding or decoding error occurs.

UnicodeEncodeError if a Unicode-related error occurs during encoding.

UnicodeDecodeError if a Unicode-related error occurs during decoding.

UnicodeTranslateError if a Unicode-related error occurs during translating.

ValueError if a function gets argument of correct type but improper value.

ZeroDivisionError if second operand of division or modulo operation is zero.

User-defined exceptions

As mentioned earlier, there are many types of exceptions built in exceptions, but it might not fit your needs. You can program your own type of exceptions if needed. To create a user-defined exception, you have to create a class that inherits from Exception.

Examples:

class BathroomError(Exception):

pass

raise BathroomError("Programmer went to the bathroom")

class NoMoneyException(Exception):

pass

class OutOfBudget(Exception):

pass

balance = int(input("Enter a balance: "))

if balance < 1000:

raise NoMoneyException

elif balance > 10000:

raise OutOfBudget

More flow control

range

If you need to iterate over a sequence of numbers, the built in function range comes in handy. range has the following parameters

range(start, stop[, step])

start The value of the start parameter (or 0 if the parameter was not supplied)

stop

The value of the stop parameter

step

The value of the step parameter (or 1 if the parameter was not supplied)

For a positive step, the contents of a range r are determined by the formula r[i] = start + step*i where i >= 0 and r[i] < stop

For a negative step, the contents of the range are still determined by the formula r[i] = start + step*i, but the constraints are i >= 0 and r[i] > stop

for i in range(5):

print(i)

It is also possible to set the range to start at another number

list(range(5,10))

list(range(0,10,3))

list(range(-10,-100,-30))

break statements

The break statement breaks out of the innermost enclosing for or while loop

break is used to terminate loops when it is encountered

Example:

for i in range(3):

if i == 2:

break

print(i)

In the above example, when i is equal to 2, the break statement terminates the loop. You will notice that the output of this does not include 2

continue statements

The continue statement will continue the iteration of a loop. This will work for both while loops and for loops.

Example:

for letter in 'python':

if letter == 'p':

continue

print 'Letter :', letter

var = 20

while var > 0:

var = var -1

if var == 10:

continue

print 'Current var:', var

print "Done"

pass statements

The pass statement is a null operations; nothing happens when it executes. It is useful in places where your code will eventually go but has not been written yet.

Example:

for letter in 'python':

if letter == 'o':

pass

print 'The pass was used above'

print 'cur letter :', letter

print "Done"

When executed, notice how the pass does not do anything. If the pass is not used along with the print statement, then it would just throw an error:

for letter in 'python':

if letter == 'o':

print 'cur letter :', letter

print "Done"

match case statements

match case was added in Python 3.10 >

The match case statement has a similar functionality as an if statement. If you’re familiar with bash, it is similar to a case statement as well.

The pseudocode for match case would look like the following:

parameter=""

match parameter:

case first:

do_something(first)

case second:

do_something(second)

case third:

do_something(third)

.............

............

case n:

do_something(n)

case _:

nothing_matched()

Example:

param='world, hello!'

match param:

case 'world, hello!':

print('world hello too!')

case 'hello world!':

print('hello to you too!')

case _:

print('no match found')

The above example should only match one case and would print out world hello too!

functions

A function is a block of code which only runs when it is called. You can pass data also known as parameters or arguments into a function.

To define a function the keyword def is used.

def function1():

print('hello function1')

To call a function, use the function name followed by parenthesis():

def function1():

print('hello function1')

function1()

Information can be passed into functions as arguments also known as parameters or args. Arguments are specified after the function name inside the parentheses. You can add as many arguments as you want by separating them with a comma.

def function1(first_name):

print(first_name + " lastname")

function1("Bob")

function1("Josh")

function1("Jack")

Multiple Arguments As stated earlier, you can have multiple arguments by using a comma:

def function1(first_name, last_name):

print(first_name + " middle name " + last_name)

function1("Bob", "Richard")

function1("Josh", "Lee")

function1("Jack", "Ma")

Arbitrary Arguments/*args

If you do not know how many arguments will be passed to your function, you can add a * before the parameter name:

def func1(*name):

print("His name is " + name[0] + " " + name[2])

func1("Jackie", "middlename", "Chan")

Keyword Arguments

You can also send arguments with key= value syntax. In this context, the order of arguments do not matter

def function1(name1, name3, name2):

print("The third name is" + name3)

function1(name1 = "Heather", name2 = "Johnny", name3 = "Richard")

Arbitrary Keyword Arguments, **kwargs

If you have a unknown amount of keyboard arguments(kwargs), just add two asterisks** before the parameter name in the function definition.

def function1(**name):

print("His name is " + name["first_name"] + " " + name["last_name"])

function1(first_name="Bruce", last_name="Lee")

Default Argument Values

You can set a default value to an argument by using the =.

def function1(food = "Pizza"):

print("I like to eat " + food)

function1("Oranges")

function1("Apples")

function1("Burgers")

function1()

function1("Pasta")

Data type arguments

You can send any data types of arguments to a function(sets, tuples, lists, dictionaries)

Using the built in type function, you can determine what type of data it outputs

Lists

def function1(food):

for x in food:

print(x)

fruits = ["apple", "oranges", "bananas"]

function1(fruits)

print(type(fruits))

tuple

def function1(num):

for x in num:

print(x)

odd = 1,3,5

function1(odd)

print(type(odd))

set

def function1(num):

for x in num:

print(x)

even = {"2", "4", "6"}

function1(even)

print(type(even))

dictionary

def function1(car):

for x in dict:

print(f"{x}: {dict[x]}")

dict = {

"brand": "Honda",

"model": "Civic",

"year": "1999"

}

function1(dict)

print(type(dict))

return

To return a function value, use return statement

def function1(x):

return 10 * x

print(function1(1))

print(function1(2))

print(function1(3))

range function

As seen earlier there are built in functions for python such as a the range function

If you need to iterate over a sequence of numbers this function comes in handy.

The syntax for range function works as the following:

range(start,stop,[step])

start

The value of the start parameter (or 0 if the parameter was not supplied)

stop

The value of the stop parameter

step

The value of the step parameter (or 1 if the parameter was not supplied)

Examples:

for i in range(10):

print(i)

for i in range(5,10):

print(i)

for i in range(5,10,2):

print(i)

recursion python also accepts function recursion, which means a defined function can call itself.

def countdown(x):

print(x)

if x == 0:

print("x reached 0")

else:

countdown(x - 1)

countdown(10)

The above example counts down from 10 and once it reaches 0 then it stops.

Another way to express the above example:

def countdown(x):

print(x)

if x > 0:

countdown(x - 1)

if x == 0:

print("x reached 0")

countdown(10)

map function

The map() function executes a specified function for each item in an iterable. The item is sent to the function as a parameter.

Syntax

map(function, iterables)

arguments

- function: a function

- iterable: sets, lists, tuples etc..

Examples So let’s say you have a list of items and you want to count the number of strings each item on that list has:

def func1(x):

return len(x)

x = map(func1, ['apples', 'oranges', 'bananas'])

print(list(x))

The above example uses map to map each of the items on list and sends it as a parameter to get the length of each item

We can do the same for the above without using map by using a loop:

x = ['apples', 'oranges', 'bananas']

b = []

for i in x:

b.append(len(i))

print(b)

Now lets say you have two lists and want to add them together:

def func1(a, b):

return a + b

x = map(func1, ['John', 'Jenny', 'Jason'], ['A', 'B', 'C'])

print(list(x))

Try doing the above without map

This would be much harder..

Lambda functions

Small anonymous functions can be created with the lambda keyword.

Syntax

lambda arguments : expression

Example:

x = lambda a : a + 5

print(x(2))

The above example adds 5 to the argument and prints the result

Lambda functions can also take multiple arguments:

x = lambda a,b : a * b

print(x(4,5))

The above example multiplies a with b and prints the result

Lets take a look at a use case for lambda

Lets say you have a list of peoples ages and you want to find people who are above the age of 20

ages = [11, 13, 17, 22, 23, 60, 90, 55, 88, 21]

over20 = list(filter(lambda age: age > 20, ages))

print(over20)

Comment Strings

In python there are two ways to create a comment for strings. You can use the # for a single line comment

Example

#this is a comment

print("hello person")

If you use three double quotes " it will create a multi-line comment. Followed with another three double quotes at the end of the comments.

Example

""" Do not do anything here

really do not do anything

this is a comment

This is multi-line comment

"""

print("Hello Multi-line comment")

Data Structures

Data structures are code structures for storing and organizing data that make it easier to modify, navigate and access information in python. As mentioned earlier, the most common data structures are the following: lists - [] tuple - () set - {} dictionary - dict { "a": "b"} This section goes into more details of data structures

More on Lists

The list data type has more options:

list.append(x)

Add an item to the end of the list.

list.extend(iterable)

Extend the list by appending all the items from the iterable.

list.insert(i, x)

Insert an item at a given position. The first argument is the index of the element before which to insert, so a.insert(0, x) inserts at the front of the list.

list.remove(x)

Remove the first item from the list whose value is equal to x. It raises a ValueError if there is no such item.

list.pop([i])

Remove the item at the given position in the list, and return it. If no index is specified, a.pop() removes and returns the last item in the list.

list.clear()

Remove all items from the list.

list.index(x[, start[, end]])

Return zero-based index in the list of the first item whose value is equal to x. Raises a ValueError if there is no such item.

The optional arguments start and end are interpreted as in the slice notation and are used to limit the search to a particular subsequence of the list. The returned index is computed relative to the beginning of the full sequence rather than the start argument.

list.count(x)

Return the number of times x appears in the list.

list.sort(*, key=None, reverse=False)

Sort the items of the list in place (the arguments can be used for sort customization, see sorted() for their explanation).

list.reverse()

Reverse the elements of the list in place.

list.copy()

Return a shallow copy of the list. Equivalent to a[:].

Using Lists as Queues

It’s possible to use a list as a queue where the first element added is the first element retrieved. Use collections.deque:

from collections import deque

queue = deque(["1", "2", "3"])

queue.append("4") # Append 4

queue.append("5") # Append 5

print(queue.popleft()) # First to arrive now leaves

print(queue.popleft()) # Second arrive now leaves

print(queue) # Remaining queue in order of arrival

List Comprehensions

List comprehensions help shorten syntax when you need to create a new list based on values of existing lists.

Syntax

newlist = [expression for item in iterable if condition == True]

The expression is the current item in the iteration but also the outcome, which you can manipulate before it ends up in a list item in the new list:

newlist = [x.lower() for x in fruits]

newlist = ['hello' for x in fruits]

The expression can also contain conditions to manipulate the outcome:

newlist = [x if x !="mango" else "apple" for x in fruits]

The condition is like a filter that only accepts the items that valuate to True

Only accept items that are not “apple”:

newlist = [x for x in fruits if x != "apple"]

The condition is optional and can be omitted:

newlist =[x for x in fruits]

The iterable can be any iterable object like a tuple,set,list,range etc.

newlist = [x for x in range(5)]

newlist = [x for x in range(5) if x < 3]

Example

fruits = ["green_apple", "red_apple", "banana", "mango"]

newlist = [x for x in fruits if "apple" in x]

print(newlist)

Without list comprehension you would need a for statement

fruits = ["green_apple", "red_apple", "banana", "mango"]

newlist = []

for x in fruits:

if "apple" in x:

newlist.append(x)

print(newlist)

The del statement

The del statement can be used to delete objects. The del statement can be used to delete variables, lists, or parts of a list.

list = [1,2,3,4,5]

del list[0]

print(list)

del list[2:4]

print(list)

del list

print(list)

Tuples

A tuple consists of a number of values separated by commas

t = 123, 456, 'ello'

print(t[0])

# You can also nest tuples

n = a, (1,2,3,4,5)

print(n)

# Tuples are immutable they cannot be changed

n[0]= 12345

# But they can contain mutable objects

x = ([1,2,3], [3,2,1])

print(x)

To create a tuple with only one item, you have to add a comma after the item, otherwise Python will not recognize it as a tuple.

tup = ("apple",)

print(type(tup))

# Not a tuple

tup = ("apple")

print(type(tup))

Sets

A set is a collection which is unordered, unchangeable, and unindexed Sets cannot have two items with the same value they will not repeat

Sets are written with curly braces {}

set = {"apple", "oranges", "banana"}

print(set)

The value of True and 1 are considered the same value in sets and are treated as duplicates

set = {"apple", "oranges", "banana", True, 1, 2}

print(set)

It is also possible to use set() constructor to create a set without using curly braces{}

set1= set(("apple", "orange", "banana")) #note the double brackets

print(set1)

Dictionaries

Dictionaries are used to store data values in key:value pairs

A dictionary is a collection which is ordered, changeable and do not allow duplicates (As of Python >= 3.7 dictionaries are ordered and < 3.7 are unordered)

Dictionaries are written in curly braces {} and have key and values

dict1 = {

"brand": "Honda",

"model": "Civic",

"year": 1989

}

print(dict1)

You can print specific values in a dictionary

dict1 = {

"brand": "Honda",

"model": "Civic",

"year": 1989

}

print(dict1["brand"])

Duplicates are not allowed:

dict1 = {

"brand": "Honda",

"model": "Civic",

"year": 1989,

"year": 2023

}

print(dict1)

The values in a dictionary can be any data type

dict1 = {

"brand": "Honda",

"model": "Civic",

"year": 1989,

"colors": ["red", "white", "blue"]

}

print(dict1)

It is also possible use the dict() constructor to make a dictionary without the curly braces {}

dict1 = dict(brand = "Honda", model = "Civic", year = 1989)

print(dict1)

Looping Techniques

When looping through dictionaries, the key and corresponding values can be retrieved at the same time when using the items() method

dict1 = dict(brand = "Honda", model = "Civic", year = 1989)

for k,v in dict1.items():

print(k, v)

When lopping through a sequence, the position index and corresponding value can be retrieved at the same time using the enumerate() function

for i, v in enumerate(['a', 'b', 'c']):

print(i, v)

To loop over 2 or more sequences at the same time, the entries can be paired with the zip() function

questions = ['name', 'age', 'favorite color']

answer = ['John', '89', 'red']

for q,a in zip(questions, answer):

print('What is your {0}? It is {1}.'.format(q,a))

To loop over a sequence in reverse, first specify the sequence in a forward direction and then call the reversed() function

for i in reversed(range(1,100,2)):

print(i)

To loop over a sequence in sorted order, use the sorted() function which returns a new sorted list while leaving the source unaltered:

fruits = ['apple', 'orange', 'apple', 'pear', 'orange', 'banana']

for i in sorted(fruits):

print(i)

Modules

Consider a module to be the same as a code library. A file containing a set of functions you want to include in your application.

To create a module just save the code you want in a file extension .py

# save code as mymod.py

def greeting(name):

print("Hello, " + name)

Now use the module we created by using the import statement:

import mymod

mymod.greeting("John")

You can also create an alias when you import a module, by using the as keyword

import mymod as mod1

a = mod1.greeting("Sally")

There are several built in modules for python, which you can import whenever you like

import sys

sys.ps1

The dir() Function

The dir() function is used to find out which names a module defines.

class Person:

name = "John"

age = 18

country = "USA"

print(dir(Person))

Packages

Python modules may contain several classes, functions, variables etc. Whereas Python packages contain several modules. In simple terms, Package in Python is a directory that contains multiple modules as files

Example:

car/ # Top level

__init__.py

honda

__init__.py

a.py

b.py

c.py

bmw

__init__.py

c.py

d.py

e.py

porche

__init__.py

f.py

g.py

h.py

The __init__.py files are required to make Python treat directories containing the file as a package. In the simplest cases the files can be an empty file, but it can also execute initialization code for the package or set the __all__ variable.

Users of the package can import individual modules from the package

import car.honda.a

An alternative way of importing the submodule:

from car.honda import a

This makes it so you can use the package without the prefix.

Importing * From a Package

One can import all modules by using from car.honda import * but this could take a long time to import all sub modules and have side effects. Instead what that does if __all__ is not defined, it only ensures that the packages car.honda has been imported and then imports whatever names are defined in the package. If the package owner defines a list of named __all__ it will take the list of module names and using from package import * it will use the listed modules.

__all__ = ["a", "b", "c"]

Input and Output

Fancier Output Formatting

To use formatted string literals you can begin a string with the f or F before opening quotes or triple quotes """. You can then write an expression between curly braces {} and characters can be referred to variables or literal values

name = 'John'

year = 2023

f '{name} was born in {year}'

The format() Method

The format() method formats the specified values and inserts them inside the string’s placeholder

The placeholder is defined using curly braces {}

Syntax

string.format(value1, value2, ...)

The values are either a list of values separated by a comma, a key=value list, or a combination of both

THe placeholders can be identified using named indexes {namehere}, numbered indexes {0}, or even empty placeholders {}

#named indexes:

a = "My name is {fname}, I'm {age}".format(fname = "Josh", age = 15)

#numbered indexes:

b = "My name is {0}, I'm {1}".format("Josh",15)

#empty placeholders:

c = "My name is {}, I'm {}".format("Josh",15)

print(a)

print(b)

print(c)

File Handling

Python can create,read,update,delete files

The key function for files is the open() function

There are four different methods for opening a file

"r" - Default- Read - Opens a file for reading

"a" - Appends - Opens a file for appending, creates a file if it does not exist

"w" - Write - Opens a file for writing, creates a file if it does not exist

"x" - Create - Creates the specified file

You can also specify if the file should be handled as binary or text mode

"t" - Text - Default. Text mode

"b" - Binary - Binary mode (images)

Reading

To read a file

f = open("file.txt")

Also to read a file

f = open("file.txt", "rt")

Because r is to read, and t is for text.

Let’s say you only want to read parts of a file

#file.txt

Hello! This is file.txt

Test1

Test2

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.read(5))

The above example will only print the first 5 characters

Reading Lines

You can return one line by using the readline() method:

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.readline())

If you using readline() twice it will read the first two lines

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.readline())

print(f.readline())

You can read the entire file by looping:

f = open("file.txt", "r")

for x in f:

print(x)

Closing files It is always good practice to close a file when you are done with it for things such as garbage collection or even having multiple files opened at once

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.readline())

f.close()

Write and Create

As mentioned earlier you can use a for append or w for write.

Append:

f = open("file.txt", "a")

f.write("Here is a new line")

f.close()

#open and read

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.read())

f.close()

Write:

f = open("file.txt", "w")

f.write("New file with new content")

f.close()

#open and read the file after the overwriting:

f = open("file.txt", "r")

print(f.read())

f.close()

New file

To create a new file as mentioned earlier you can using either x, a, w if the file does not exist. x will throw an error if file already exists

f = open("file.txt", "x")

# create file if does not exit, overwrite if does exist

f = open("file.txt", "w")

# create file if does not exist, append if does exist

f = open("file.txt", "a")

Delete

To delete a file, you must use the os module using the os.remove() method

import os

os.remove("file.txt")

Check if file exists To avoid errors, you might want to check if the file exists first

import os

if os.path.exists("file.txt"):

os.remove("file.txt")

else:

print("file.txt does not exist")

Delete directory

To delete an entire directory, us the os.rmdir() method

import os

os.rmdir("textdir")

Python JSON

JSON is a popular data interchange format which makes it easy to store and exchange data.

Python has a built in package called json to use it just import the module

import json

Parse JSON

If you have a JSON string, you can parse it by using json.loads() method

import json

# JSON:

x = '{ "name":"Jenny", "age":18, "city":"San Francisco"}'

# parse x:

y = json.loads(x)

# the result is a Python dictionary:

print(y["age"])

Convert from Python to JSON

If you have a Python object, you can convert it into a JSON string by using the json.dumps() method

import json

# a Python object dictionary:

x = {

"name": "Jenny",

"age": 18,

"city": "San Francisco"

}

# convert into JSON:

y = json.dumps(x)

# the result is a JSON string:

print(y)

You can convert all types of objects:

string

integer

list

dictionary

tuple

float

True

False

None

When you convert from Python to JSON, Python objects are converted into the Javascript equivalent. The following is a table for the conversion

| Python | JSON |

|---|---|

| string | String |

| integer | Number |

| list | Array |

| dictionary | Object |

| tuple | Array |

| float | Number |

| True | true |

| False | false |

| None | null |

Lets convert all types

import json

x = {

"name": "Jenny",

"age": 18,

"married": True,

"divorced": False,

"children": ("John","Annie"),

"pets": None,

"cars": [

{"model": "Honda Accord", "mpg": 25.5},

{"model": "Ford F150", "mpg": 18}

]

}

print(json.dumps(x))

Formatting Results

The above example prints in JSON string but it is not easy to read. The json.dumps() method has parameters to make it easier to read

import json

x = {

"name": "Jenny",

"age": 18,

"married": True,

"divorced": False,

"children": ("John","Annie"),

"pets": None,

"cars": [

{"model": "Honda Accord", "mpg": 25.5},

{"model": "Ford F150", "mpg": 18}

]

}

# Indent by 4 to make it easier to read

print(json.dumps(x, indent=4))

You can also use separators default value is (", ", ": ") command and space to separate each object and a colon and space to separate keys from values. You can use separators to change the default separators

import json

x = {

"name": "Jenny",

"age": 18,

"married": True,

"divorced": False,

"children": ("John","Annie"),

"pets": None,

"cars": [

{"model": "Honda Accord", "mpg": 25.5},

{"model": "Ford F150", "mpg": 18}

]

}

# use . and a space to separate objects, and a space, a = and a space to separate keys from their values:

print(json.dumps(x, indent=4, separators=(". ", " = ")))

Order Results

The json.dumps() method also has a way to order keys form key value to sort by alphabetical by using sort_keys

import json

x = {

"name": "Jenny",

"age": 18,

"married": True,

"divorced": False,

"children": ("John","Annie"),

"pets": None,

"cars": [

{"model": "Honda Accord", "mpg": 25.5},

{"model": "Ford F150", "mpg": 18}

]

}

# Indent by 4 to make it easier to read

print(json.dumps(x, indent=4, sort_keys=True))

Errors and Exceptions

Syntax Errors

Syntax errors are also known as parsing errors. The parser repeats the offending line and displays a arrow pointing at the earliest point in the line where the error was detected.

Example:

while True print('hello world')

The above example will show an error because the : is missing before the arrow

Exceptions

Errors detected during an execution is called an exception and are not unconditionally fatal.

There are several different types of exceptions the built in exceptions will always print the exception during the error. This will not always be true for user-defined exceptions.

10 * (1/10)

5 + hello*3

'10' + 10

The above example shows 3 different types of built in exceptions

Handling Exceptions

It is possible to write programs to handle selected exceptions.

The try block lets you test a block of code for errors

The except block lets you handle the error

The else block lets you execute code when there is no error.

The finally block lets you execute code, regardless of the result of the try- and except blocks.

try:

print(x)

except:

print("An exception occurred")

The above example try block raises an error, the except block will be executed. If you use the try block by itself, it will raise an error.

You can have as many exception blocks as you want. The above example was a NameError so we can raise an exception when that happens.

try:

print(x)

except NameError:

print("Variable x is not defined")

except:

print("Not a NameError but another error")

You can use the else keyword in the block if there are no errors raised:

try:

print("Hello World")

except:

print("Error occurred")

else:

print("Nothing went wrong! :)")

The finally block will be executed if the try block raises an error or not.

try:

print(x)

except:

print("Error occurred")

finally:

print("The 'try except' has finished")

Let’s say we want to write to a file that is not writable:

try:

f = open("file.txt")

try:

f.write("World Hello")

except:

print("Cannot write to file")

finally:

f.close()

except:

print("Error with opening file")

Raising Exceptions

To raise or throw an exception use the raise keyword

x = -1

if x < 0:

raise Exception("No numbers below zero")

If you need to determine whether an exception was raised or not but do not intend to handle it, simply re-raise the exception

try:

raise NameError('World Hello')

except NameError:

print('NameError said World Hello')

raise

Exception Chaining

If an unhandled exception inside of an except block, it will have the exception being handled attached to it and included in the error message:

try:

open("elloworld")

except OSError:

raise RuntimeError("unable to handle error")

To indicate that an exception is a direct consequence of another, the raise statement allows an optional from clause

def func():

raise ConnectionError

try:

func()

except ConnectionError as theexception:

raise RuntimeError('Failed to open') from theexception

It also allows disabling automatic exception using from None

try:

open('elloworld')

except OSError:

raise RuntimeError from None

User-defined Exceptions

One can create a custom defined exception by creating a class which is talked about later.

class CustomError(Exception):

pass

raise CustomError("Example of Custom Exception")

Raising and Handling Multiple Unrelated Exceptions

Sometimes there are situations where it is necessary to report several exceptions that have occurred. The builtin ExceptionGroup wraps a list of exceptions so that they can be raised together.

def f():

excs = [OSError('error 1'), SystemError('error 2')]

raise ExceptionGroup('Problems have occurred', excs)

try:

f()

except Exception as e:

print(f'caught {type(e)}: e')

You can also use except* instead of except to handle only exceptions within that group to match a certain type.

def f():

raise ExceptionGroup(

"group1",

[

OSError(1),

SystemError(2),

ExceptionGroup(

"group2",

[

OSError(3),

RecursionError(4)

]

)

]

)

try:

f()

except* OSError as x:

print("There were OSErrors")

except* SystemError as x:

print("There were SystemErrors")

Enriching Exceptions with Notes

You can also add notes to exceptions by using add_note()

try:

raise TypeError('Error')

except Exception as x:

x.add_note('Note1')

x.add_note('Note2')

raise

Classes

Python is an object oriented language; almost everything in Python is an object. Classes encapsulate data (attributes) and behavior (methods) into a single unit, allowing you to create reusable and organized code.

Create Class

To create a class use the keyword class

class ExampleClass:

x = 10

Creating Attributes

Attributes are variables that hold data associated with the class. They define the characteristics or properties of objects created from the class. Attributes can be defined within the class and accessed using the dot notation.

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

In the example above, the name and age attributes are defined within the Person class.

The __init__() method is a special method called the constructor, used to initialize the attributes when an object is created.

Methods

Methods are functions defined within a class that define the behavior of the objects created from the class.

class Circle:

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def area(self):

return 3.14 * self.radius ** 2

In the above example, the Circle class has an area method that calculates the area of a circle based on its radius

Constructor

As mentioned earlier, the constructor__init__() is a special method that gets called when an object is created from the class. t’s used to initialize attributes and set their initial values. The first parameter of __init__ is typically self, which refers to the instance being created

Instance

An instance is an object created from a class. Each instance has its own set of attributes and can call the methods defined within the class.

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def greet(self):

return f"Hello, my name is {self.name} and I'm {self.age} years old."

# Creating instances of the Person class

person1 = Person("Alice", 30)

person2 = Person("Bob", 25)

# Accessing attributes and calling methods on instances

print(person1.name)

print(person2.age)

# Calling the greet method

print(person1.greet())

print(person2.greet())

In the above example, the Person class is defined with an __init__ constructor method that initializes the name and age attributes. It also has a greet method that returns a greeting message using the attributes. Instances of the Person class, person1 and person2, are created and then attributes are accessed and methods are called on these instances.

Inheritance

Inheritance allows you to create a new class that inherits attributes and methods of existing classes(calling a class from another class). The new class is called a subclass or derived class, and the original class is called the superclass or base class. Subclasses can override or extend the behavior of the superclass.

class Address:

def __init__(self, street, city, state, zip_code):

self.street = street

self.city = city

self.state = state

self.zip_code = zip_code

def display(self):

return f"{self.street}, {self.city}, {self.state} {self.zip_code}"

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age, address):

self.name = name

self.age = age

self.address = address # Here, we're storing an Address object

def greet(self):

return f"Hello, my name is {self.name} and I live at {self.address.display()}."

# Creating an Address instance

home_address = Address("123 Main St", "Cityville", "CA", "12345")

# Creating a Person instance and passing the Address instance as an argument

person = Person("Alice", 30, home_address)

# Calling methods on the Person instance and its associated Address instance

print(person.greet())

# Output: Hello, my name is Alice and I live at 123 Main St, Cityville, CA 12345.

In the above example, we have two classes: Address and Person. The Person class defines a person with their name,age, and an Address instance passed as an argument during initialization. The greet method in the Person class then calls the display method from the Address instance associated with that person

Brief Tour of the Standard Library

Below we will go over some standard libraries within python which can be useful

Operating System Interface

The os module provides several functions for interacting with the operating system.

Here are some of the commonly used functionalities provided by the os module:

Working with Files and Directories:

os.getcwd(): Get the current working directory.

os.chdir(path): Change the current working directory.

os.listdir(path): Get a list of files and directories in a given path.

os.mkdir(path): Create a new directory.

os.rmdir(path): Remove an empty directory.

os.remove(path): Delete a file.

Path Manipulation:

os.path.join(path, *paths): Join multiple path components to create a full path.

os.path.exists(path): Check if a path exists.

os.path.isfile(path): Check if a path points to a file.

os.path.isdir(path): Check if a path points to a directory.

Process Management:

os.system(command): Run a command in the system's shell.

os.spawn* and os.exec*: Lower-level process control functions.

os.kill(pid, signal): Send a signal to a process.

Environment Variables:

os.environ: A dictionary containing the environment variables.

os.getenv(varname): Get the value of a specific environment variable.

os.putenv(varname, value): Set the value of an environment variable.

File Permissions:

os.chmod(path, mode): Change the permissions of a file.

os.stat(path): Get information about a file (size, timestamps, permissions).

Platform Information:

os.name: A string indicating the name of the operating system ("posix", "nt", etc.).

os.uname(): Get system-dependent version information.

- Working with Files and Directories

import os

# Get current working directory

current_dir = os.getcwd()

print("Current directory:", current_dir)

# Create a new directory

new_dir = os.path.join(current_dir, "new_folder")

os.mkdir(new_dir)

# List files and directories in the current directory

contents = os.listdir(current_dir)

print("Contents of current directory:", contents)

# Remove a directory

os.rmdir(new_dir)

- Path Manipulation ```python import os

path1 = “/path/to” path2 = “file.txt”

full_path = os.path.join(path1, path2) print(“Full path:”, full_path)

print(“Does the path exist?”, os.path.exists(full_path)) print(“Is it a file?”, os.path.isfile(full_path)) print(“Is it a directory?”, os.path.isdir(full_path))

3. Running Shell Commands:

```python

import os

# Run a command using the system's shell

os.system("ls -l")

# Use subprocess module for more control

import subprocess

result = subprocess.run(["ls", "-l"], capture_output=True, text=True)

print(result.stdout)

- Environment Variables ```python import os

Get specific environment variable

home_dir = os.getenv(“HOME”) print(“Home directory:”, home_dir)

Set an environment variable (note: this doesn’t persist)

os.environ[“MY_VARIABLE”] = “my_value” print(“MY_VARIABLE:”, os.getenv(“MY_VARIABLE”))

5. File permissions

```python

import os

file_path = "example_file.txt"

# Change file permissions

os.chmod(file_path, 0o644) # Change to read/write for owner, read for others

# Get information about a file

file_info = os.stat(file_path)

print("File size:", file_info.st_size, "bytes")

File Wildcards

The glob module has a function for making file lists form directory wildcard searches

import glob

glob.glob('*.py')

The above example searches for *.py in directory

Command Line Arguments

Often in Python you might want to create a script that takes command line arguments. To do this it involves the sys module or the built in argparse module.

- The

sysmodule provides aargvattribute wheresys.argv[0]is the script name and the following are other arguments

# script_name.py

import sys

def main():

script_name = sys.argv[0]

arguments = sys.argv[1:]

print("Script name:", script_name)

print("Arguments:", arguments)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

You can then run the script with command line arguments:

python script_name.py arg1 arg2 arg3

- The

argparsemodule provides a mode structured way to handle command-line arguments and offers features like argument validation and help messages

#script_name.py

import argparse

def main(args):

print("Arguments:", args.arg1, args.arg2)

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="A script with command-line arguments.")

parser.add_argument("arg1", help="Description for arg1")

parser.add_argument("arg2", help="Description for arg2")

args = parser.parse_args()

main(args)

You can then run the script with command line arguments using the -h for help or --help flag.

python script_name.py -h

python script_name.py --help

python script_name.py value1 value2

Error Output Redirection and Program Termination

The sys module also has attributes for stdin, stdout, and stderr.

- The

stdinstream is used to read input from the user or from a file

import sys

def main():

print("Enter your name:")

name = sys.stdin.readline().strip()

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The above example, the script reads a line from the standard input (keyboard or piped input) using sys.stdin.readline(). The strip() method is used to remove the newline character from the input.

- The

stdoutstream is used to write output to the console or to a file. ```python import sys

def main(): print(“This is a message on stdout.”)

if name == “main”: main()

The above example, the script uses `print()` to write a message to the standard output.

3. The `stderr` stream is used to write error messages or diagnostic information separately from regular output.

```python

import sys

def main():

try:

x = 10 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("An error occurred!", file=sys.stderr)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The above example, an error message is printed to the standard error stream using the file=sys.stderr argument with the print() function.

String Pattern Matching

The re module provides regular expression tools for advanced string processing.

import re

re.findall(r'\bf[a-z]*', 'which foot or hand fell fastest')

re.sub(r'(\b[a-z]+) \1', r'\1', 'cat in the the hat')

Dates and Times

The datetime module in Python is a built-in module that provides classes for working with dates, times, and time intervals. It’s a powerful tool for handling various time-related operations, including date arithmetic, formatting, parsing, and more. The module offers a range of classes and functions that make it easier to work with dates and times in a consistent and reliable manner.

datetimeClass: This class represents a combination of date and time, including year, month, day, hour, minute, second, and microsecond.

from datetime import datetime

current_datetime = datetime.now()

print("Current datetime:", current_datetime)

dateClass: Represents a date (year, month, and day) without time.

from datetime import date

current_date = date.today()

print("Current date:", current_date)

timeClass: Represents a time of day, including hours, minutes, seconds, and microseconds.

from datetime import time

specific_time = time(12, 30, 0)

print("Specific time:", specific_time)

timedeltaClass: Represents the difference between two dates or times.

from datetime import timedelta

one_day = timedelta(days=1)

tomorrow = current_date + one_day

print("Tomorrow:", tomorrow)

- Formatting and Parsing: The

strftimemethod is used to formatdatetimeobjects as strings, and thestrptimefunction is used to parse strings intodatetimeobjects. ```python

formatted_date = current_date.strftime(“%Y-%m-%d”) parsed_date = datetime.strptime(“2023-08-13”, “%Y-%m-%d”)

6. Timezones: The `timezone` class allows you to work with time zones. The `pytz` library is commonly used to handle time zones effectively.

```python

import pytz

from datetime import datetime

tz = pytz.timezone("America/New_York")

localized_time = datetime.now(tz)

print("Localized time:", localized_time)

Data Compression

You can compress files using both tarfile and zipfile modules

Using tarfile:

import tarfile

# Creating a Tar archive

with tarfile.open("archive.tar", "w") as tar:

tar.add("file1.txt")

tar.add("file2.txt")

# Extracting files from a Tar archive

with tarfile.open("archive.tar", "r") as tar:

tar.extractall("extracted_folder")

Using zipfile:

import zipfile

# Creating a Zip archive

with zipfile.ZipFile("archive.zip", "w") as zipf:

zipf.write("file1.txt")

zipf.write("file2.txt")

# Extracting files from a Zip archive

with zipfile.ZipFile("archive.zip", "r") as zipf:

zipf.extractall("extracted_folder")

Performance Measurement

One can measure time it takes to run code.

from timeit import Timer

print(Timer('t=a; a=b; b=t', 'a=1; b=2').timeit())

Quality Control

unittest is a built-in testing framework in Python that allows you to write and execute test cases for your code. It provides a structured and organized way to automate the testing process, ensuring that your code behaves as expected and remains stable as you make changes. Automated testing helps catch bugs and regressions early in the development cycle.

Here are the key concepts and components of the unittest framework:

-

Test Case Class: You create test cases by subclassing the unittest.TestCase class. Each test case is a class that contains methods representing individual test scenarios.

-

Test Methods: Test methods are named with a “test_” prefix. They contain assertions that verify the behavior of the code under test.

-

Assertions: Assertions are methods provided by the unittest.TestCase class to check whether the expected conditions are met. Common assertions include assertEqual, assertTrue, assertFalse, assertRaises, and more.

-

Test Discovery: The unittest framework can automatically discover and run test cases in your codebase. Test discovery is usually initiated using the unittest command-line interface or test runners like unittest.TextTestRunner.

#add.py

import unittest

def add(a, b):

return a + b

class TestAddFunction(unittest.TestCase):

def test_add_positive_numbers(self):

result = add(2, 3)

self.assertEqual(result, 5)

def test_add_negative_numbers(self):

result = add(-2, -3)

self.assertEqual(result, -5)

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

In the above example:

- We have a f unction

addthat adds two numbers - We create a test cases class

TestAddFunctionthat subclassesunittest.TestCase - Inside the test cases class, we define methods with the

test_prefix. These methods use assertions to verify the behavior of theaddfunction. - We use the

unittest.main()function to discover and run the test cases when the script is executed

Run the script:

python add.py

It is common practice to have unittest in your code espeically for very long lines of code. Getting used to having unit tests in your code can take some time to learn but will help you as a developer along the way.

Logging

Logging in Python is a built-in module that provides a flexible and structured way to manage and record log messages during the execution of a program. Logging is essential for debugging, monitoring, and understanding the behavior of your application. It allows you to control the verbosity of messages and easily direct them to various outputs, such as console, files, or external services.

Here are the key components and concepts related to logging in Python:

Log Levels: Log messages are categorized into different levels, indicating their importance and severity. The standard log levels, in increasing order of severity, are: DEBUG, INFO, WARNING, ERROR, and CRITICAL.

Loggers: Loggers are used to emit log messages. You create a logger object to represent different parts of your application. Loggers allow you to categorize and organize your log messages.

Handlers: Handlers determine where log messages are sent. They define the output destinations for the log messages, such as the console or log files. You can attach one or more handlers to a logger.

Formatters: Formatters define the layout and structure of log messages. They format log records to include information like the timestamp, log level, module name, and the actual log message.

import logging

# Configure the logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG,

format='%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

# Create a logger

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

# Log messages at different levels

logger.debug('This is a debug message')

logger.info('This is an info message')

logger.warning('This is a warning message')

logger.error('This is an error message')

logger.critical('This is a critical message')

- We configure the logging using basicConfig, setting the minimum log level to DEBUG and specifying a log message format.

- We create a logger named ‘my_logger’.

- We use the logger to emit log messages at different levels.

By default, log messages with a severity level equal to or higher than the specified level will be recorded. You can customize the log level, format, and handlers to suit your needs. For instance, you might configure different loggers for different parts of your application, each with its own set of handlers and formats.

Stacks & Queues

Stacks: Image you have a stack of books. You can only add or remove books from the top of the stack, one at a time. It’s like a big tower of books, and you can only work with the book on top. When you want to add a book, you put it on top. When you want to take a book away, you always take the one on the top first. Stacks work likea pile of things where you can only touch the top item.

Let’s see an example of stacks. Let’s say you have a stack of plates where you can only add a plate on top of the stack or remove the top plate. This is called Last in, First-Out (LIFO)

# Create a stack using a list

stack = []

# Pushing (adding) items onto the stack

stack.append("plate1")

stack.append("plate2")

stack.append("plate3")

# Popping (remove) items from the stack

removed_plate = stack.pop()

print("Removed plate:", removed_plate)

Queues Now, think about a line of people waiting for ice cream. The first person who arrives is the first person to get ice cream. It’s like when you’re waiting for your turn to play a game or get a treat. In a queue, you go in order, one person after another. No one can jump ahead; you have to wait your turn.

So now let’s say there’s a line of people waiting for a bus. The first person who arrives first gets on the bus first. THis is called First in, First-Out(FIFO).

# import the queue class from the queue module

from queue import Queue

# Creating a qeuue

queue = Queue()

# Add items to the queue

queue.put("Person1")

queue.put("Person2")

queue.put("Person3")

# Remove items from queue

removed_person = queue.get()

print("Removed person:", removed_person)

You can also do this without using the queue class:

# Create an empty list representing the queue

queue = []

# Add items to the queue by appending them to the end of the list

ueue.append("person1")

queue.append("person2")

queue.append("person3")

# Remove items from the queue by popping them from the front of the list

removed_person = queue.pop(0)

print("Removed person:", removed_person)

Notice how this is similar to the stack example but instead of removing the last person, we remove the first person using queue.pop(0).

Binary Tree & Tree Nodes

Binary Trees: Imagine you have a family tree, like a chart that shows how your family members are related. In a binary tree, it’s a bit like that, but with some rules:

- Each person (or node) has only two children. You can think of them as left and right.

- Just like you have a family tree starting with your grandparents, then your parents, and so on, in a binary tree, there’s one special person at the very top called the “root.”

A binary tree is a data structure where each element is called a “node”, and each node can have up to two children. The top node is called the “root”, and it branches out into child nodes, which can further branch out into their own child nodes, forming a tree-like structure.

Example:

class TreeNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.left = None # The left child

self.right = None # The right child

# Create a binary tree

root = TreeNode(1)

root.left = TreeNode(2)

root.right = TreeNode(3)

root.left.left = TreeNode(4)

root.left.right = TreeNode(5)

In this code:

- We define a

TreeNodeclass to represent each node in the binary tree. Each node has a value and can have aleftchild and arightchild. - We create a binary tree by creating nodes and connecting them to form the tree structure.

Tree Nodes A tree node is like a card with some information on it. In a family tree, it might have the name of a family member. In a binary tree, each node has some information(like a number) and can have two children.

A tree node, is a building block of a binary tree. It contains some data in a form of value and can have references to its left and right children. Each node is like a part of a puzzle, and when you put all the puzzle peices(nodes) together, you get the whole binary tree.

So using the binary tree example you can access the nodes in the following example:

class TreeNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.left = None # The left child

self.right = None # The right child

# Create a binary tree

root = TreeNode(1)

root.left = TreeNode(2)

root.right = TreeNode(3)

root.left.left = TreeNode(4)

root.left.right = TreeNode(5)

# Accessing values of nodes

print("Root value:", root.value) # Output: Root value: 1

print("Left child of root:", root.left.value) # Output: Left child of root: 2

print("Right child of root:", root.right.value) # Output: Right child of root: 3

Binary tree height balance

The height balance of a binary tree refers to how balanced or skewed the tree is in terms of the heights of its subtrees. In a balanced binary tree, the difference in the height between the left and right sub trees of any node is lmited, typically to a small value like 1.